The Pros and Cons of Publishing by Premiere

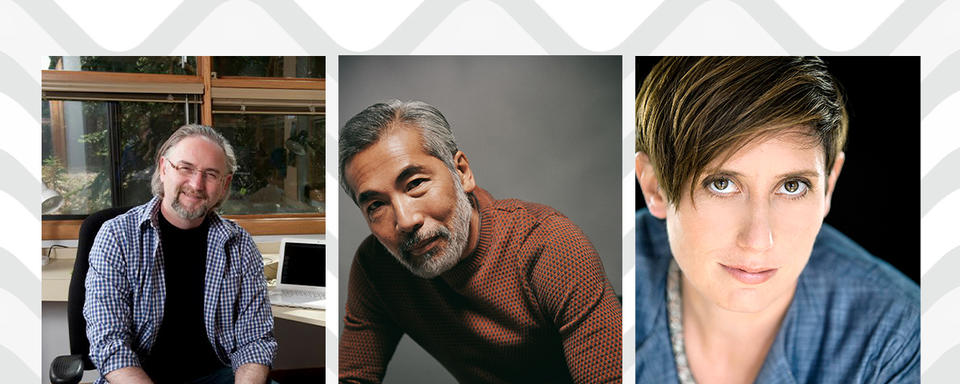

Q&A with Erin Shields, Vern Thiessen, and Hiro Kanagawa

What’s the sweet-spot publishing date of a new play? Premiere can be an advantageous moment for the book launch, but if playwrights are in the midst of production discoveries and rewrites, juggling two significant projects can risk impacting both processes. Printing the post-production draft ensures all premiere changes are reflected in the text, but does it miss a sense of occasion or celebration?

We decided to dive into the pros and cons with playwrights familiar with the process: Erin Shields, Vern Thiessen, and Hiro Kanagawa.

1. What advice do you have for playwrights deciding if they want to publish by premiere or wait until after opening?

Erin: First off, I would say having the opportunity to publish at all is a real honour. There are so many new plays written and produced every year in this country and very few of them get published. I’ve found that decisions about when to publish aren’t generally up to the playwright. Standard practice tends to be to wait until after the premiere before publishing. Usually that isn’t until a year or so after the premiere—when the publisher has space in their schedule to publish the play. By that point, the life-or-death feeling behind each rewrite has faded so you can revisit the text with a bit more awareness. However, the momentum around the play has also faded, which makes it feel distant from the interaction between audience and performers.

Vern: Getting published is hard—no matter how successful you are. Take the publication always, because the offer may never come again. It used to be that you would only GET published after premiere. That's changed a bit, but few drama publishers will do it. They want a produced play to publish. [Vern's play Bluebirds was published prior to premiere.]

Hiro: In the final analysis, it's hard to recommend publishing by premiere. I just don't see that there are any notable benefits. You might sell a few more books during the run than you would if you wait until after the show closes, but it's marginal. If you do publish by premiere, you really need to include a disclaimer stating that the script may differ significantly from the premiere production.

2. If you've published by premiere: what (or who) was the deciding factor? Was it a nice souvenir of a moment in time or a sprint you regret?

Erin: I published Paradise Lost in time for the opening at The Stratford Festival. In that case, it was excellent timing. The rep schedule meant the rehearsal process was greatly extended. There was more time to write throughout the process and into previews so I had very few last-minute rewrites. We also coupled the book launch with a talk I gave at a Festival Forum Event so I sold and signed books in the bookstore after the talk. Professor Paul Stevens, who advised me in the process and wrote the program note which doubled as a forward for the printed text, was also at the talk. And the audience went to see the play afterwards. It really felt like a proper book launch and was a nice souvenir of that show.

Hiro: Because Forgiveness was based on an award-winning and best-selling book, I felt that a lot of people who loved the book might come see the play and that they might then be interested in comparing the book with the stage adaptation. That was basically the impetus behind publishing in time for the premiere. I don't necessarily regret the decision, but I wouldn't do it again. It's hard to shake the feeling that there is something "definitive" about a published book, and that's just not the case with a published play. With Forgiveness, people who saw the premiere and bought the published script are not only going to see major differences between the script and the original book, they're going to see major differences between the script and the show that they saw!

3. If you've waited until after premiere: what (or who) was the deciding factor? What draft or round of rewrites made you go, "This is it! This is the final print draft"?

Erin: With all of my other plays, I’ve published after the premiere. For me, the published script is a record of the premiere so I don’t do a lot of rewrites post-opening unless there is something I know I want to fix. If the play has a second production and I’m in the room, I continue to write. I update the published text when that opportunity becomes available, but also, if someone is going to do the play, I give them the most updated script to work from. A playscript is always an evolving document.

Vern: You can always change it in a second edition, which I have done many times. Getting published is huge, because it opens the door to awards and prizes and the Public Lending Right, things that are not available without publication. That's the real reason to do it.

Hiro: With my previous plays, I just went along with the general Playwrights Canada Press policy of publishing after the premiere production. The final print draft in those cases corresponded very closely with the play that premiered, and I don't recall any feelings of finality or completion. If you really think about what plays actually are, any printed script ought to be viewed ideally as a blueprint that looks forward to potential future productions. A play script is not the same as a novel or a published screenplay, it's not ever "locked" and shouldn't be considered a definitive record looking back at something that happened in the past.

4. The premiere audience vs. the published play audience: are they different, or are you hoping they're different?

Erin: The main difference between the live audience and published play audience is distance to the performance. People who love plays watch plays. People who love plays read plays. I, myself, love reading plays. It’s a way I can access other playwrights’ work both in Canada and abroad when I can’t see it live. I also love to see the choices playwrights make around formatting and punctuation. When I lived in Montreal, I read five plays a week because the National Theatre School has a magnificent theatre library. I’m really missing it since I’ve moved back to Toronto.

Vern: No one reads plays unless they are forced to via a course/class or if they are theatre people. So there is a very limited audience there for reading. Its main value is becoming intellectual property that you can leverage for other things—film/tv adaptations, awards, prizes, and PLR. And of course, it's a pride thing—very, very few plays get published. If yours does, you're lucky.

Hiro: In a country like Canada with its vast distances between cities, the published play audience is probably very different from the premiere audience. When you consider that second or third productions of new Canadian plays are exceedingly rare, the published play audience might be very different from anyone who has ever seen the play actually performed.

5. The adage "New plays are never finished, they just open": Is that your philosophy and approach?

Erin: Yes. I’d say there’s truth in that. However, there is a feeling of completion when the show opens. Like you’ve climbed a mountain and can look back at the journey and think, “Wow—this play has really come a long way. And wow, that was a steep climb. And holy shit, I’m exhausted so you actors are going to have to take it from here because that’s all of I’ve got and I’m glad you guys are still into it but I’m probably not going to come back again because the prospect of reliving this play from my seat in the audience again will probably break me.”

Vern: My adage is "Plays are never finished, they are only abandoned."

Hiro: This became something of a mantra during the recent premiere of Forgiveness at the Arts Club in Vancouver. Significant changes were being made on a near-daily basis, even as previews began. I actually looked up the origins of this adage for my playwright's notes for the subsequent Theatre Calgary opening. While there are various attributions—Paul Valéry, Anaïs Nin to name just a couple—in the theatrical context it appears to originate with American director Alan Schneider. In 1962, as he was about to premiere Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? on Broadway, Schneider remarked to a journalist, “I don’t know of any perfect play. A work of art is never completed, only abandoned. The only perfect play is a dead play.” I agree completely for a medium like theatre in which a live interaction among actors and with the audience is a major component of how the artwork is experienced and how the meaning of it is formed.

Comments