On creating, collecting, and studying immigrant theatre in Canada

An interview with Yana Meerzon about her new essay collection and anthology

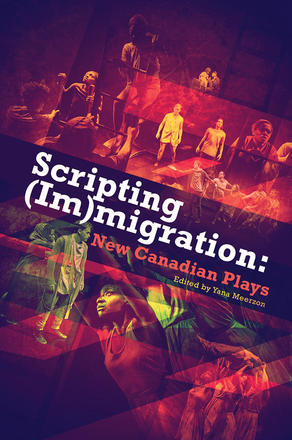

The new essay collection, Theatre and (Im)migration, and its companion anthology Scripting (Im)migration, both edited by Yana Meerzon, shine a bright light on the impact that immigrant artists have made and continue to make on the development of Canadian theatre, from themes, characters, and world issues to financial structures and artistic techniques. While the essays demonstrate how the increased presence of immigrant theatre artists actively contributing to English and French Canadian theatre prompt their audiences to rethink fundamental concepts of nationalism and multiculturalism, the plays take a look at communication, historic moments, the immigrant and refugee experiences in Canada, accents, and more.

Read our interview with Yana Meerzon, a professor at the University of Ottawa’s Department of Theatre, to learn about all of the work that was put into creating these two volumes and the importance to Canadian theatre.

How did you start working on these books? What were your challenges?

I structured the books in three sections—historical, theoretical, and practical. Of course, it was impossible to cover all aspects of very complex histories under one cover. Still, my idea was to draw as diverse a picture as possible and to provide space to as many communities and immigrant theatre practices as there are in Canada. I imagined these books as one project—if certain geographies or practices were not represented in one volume, they were to be reflected in the other. For example, the scholarly volume does not have a separate article on Russian and East European theatre practices in Canada, but in the play anthology there is a musical written by Lola Xenos that looks at these experiences.

I also wanted to acknowledge the difference between English and French theatre traditions in Canada, and to demonstrate that to speak about theatre and immigration in Canada one must take into account these two cultural perspectives and practices. Integrating into these distinct cultures can take very different strategies of understanding. However, when it comes to the themes, issues, and aesthetic dilemmas immigrant theatre artists raise in their work, we can see many similarities between them. Working on this project I discovered that, when it comes to immigration, there are more than two solitudes. There are many constellations and partnerships that immigrant artists create; their thinking goes beyond English/French dualities or even beyond what Alan Filewod calls trialetics—English/French/Indigenous connections.

Ultimately, what do you want these books to show readers?

These books demonstrate how much immigration has influenced the making of Canadian theatre. I did not plan to paint a rosy picture of everybody living peacefully together—things have been tough for many people and we know that—but it was important to show that, despite many difficulties, there is hope.

It was important for me to collect articles that would look at how immigration and immigrant theatre artists have been treated in Canada both historically and currently. If you read those chapters chronologically, you can also see how the face of immigration has been changing from one decade to another, how immigrant theatre practice changed to reflect post-colonial and independence movements, economic and cultural crisis, wars, and other atrocities that the world was facing at those times.

What was your process for delegating which essays appeared in Theatre and (Im)migration?

I wanted to create a rich and diverse representation of Canadian scholarship. I asked both established and emerging scholars to contribute to this book. I also wanted to mix its genres—the essays range from historical to highly theoretical, and there are personal statements created by artists and researchers, self-reflections, and interviews, too.

Secondly, it was important for me to show that immigration concerns every Canadian, from those who can call themselves first-generation immigrants, like myself, to those whose families moved to Canada several generations ago. The articles are written by scholars who have recently experienced displacement and by those who can identify with it only by approximation.

Finally, the contributions vary in their methodological approaches—some scholars come from the fields of literature or social studies; others are theatre historians or theoreticians of performance studies. Some preferred to work with archival documents, whereas others were more comfortable articulating their own artistic practice.

Most importantly, the book provides space for immigrant theatre artists and researchers to talk about their vision for theatre from the perspective of the rehearsal hall and auditorium, as well as from their personal, everyday experiences of intercultural encounters, specifically when those are essential to the work they started in Canada.

How do you imagine Theatre and (Im)migration being studied now and five to ten years from now?

This is a historical project—both in terms of what it covers and how it looks at the problem. As an immigrant myself, I have been searching for a better understanding of what Canada is or imagines itself to be as a nation since my arrival to Toronto in 1996. To a certain extent, this project is an attempt to explain to myself and my students what this country is or imagines itself to be through theatre, following the work of Alan Filewod, Ric Knowles, Erin Hurley, and Barry Freeman, among others. What I discovered working on this project and over two decades living in Canada is that Canadian theatre changes and evolves with every new voice featured on its stages. That is why I came up with the image of shifting and shimmering maps that can reflect what was and is the project of immigrant theatre in Canada. This type of map has both vertical and horizontal dimensions; it is something that constantly changes, shifting its ideological and artistic accents. It reflects how every new generation of artists that comes into the country understands and imagines what their new place is and can be. In five or more years, I hope these books will continue to be used in Canadian theatre history courses and serve to demonstrate how the diversity of Canadian theatre came to life. I also hope there will be other books and special issues that will continue to create a record of how immigration has been influencing Canadian theatre.

How did you decide what plays to include in Scripting (Im)migration?

I have been looking for scripts about immigration to Canada for many years, starting in 2001 when I was involved as a dramaturge in staging Silvija Jestrovic’s play Not My Story, directed by Dragana Varagic for the Toronto Fringe. This experience singled out many themes that interest me in contemporary plays in general, and in the dramatic texts about migration. I am a big fan of what we call post-dramatic plays, in which language functions as the major focal point of the writer’s experiment. Thus, I was searching for scripts that not only provide the most urgent way to address this topic but that also focus on language as the tool and the territory of their experimentation.

The book includes two scripts written in stylized language, almost like poetry; it has two plays that engage with the practice of multilingualism; it has a script that uses a documentary theatre style; and it also contains a libretto for a musical with Brechtian songs. My rationale for selecting those scripts was very simple—I wanted to find and showcase those plays written about immigration or by immigrant artists that combine the most urgent issues related to migration and that use language in the most artistically unorthodox way.

How do the selected plays describe the “current moment” of Canadian theatre?

The plays chosen for this collection indicate a shift in making socially engaged theatre in Canada. They all challenge the practices of realistic representation of displacement in which the characters emerge as suffering subjects without hope. Marked by the good intentions of their authors, such scripts often tend to patronize their own subjects, sometimes even without realizing what they are doing. All of the plays chosen for this book avoid this kind of realism and engage in various artistic experiments. This indicates maturity of Canadian dramaturgy about migration; it demonstrates that unlike the earlier immigrant artists who were constantly negotiating the place of immigrant subjects on stage, today’s theatre has recognized first- or second-generation Canadians as its legitimate subject or character. This is not an exception; it is a rule. With this assumption in mind, many theatre artists can now focus on the questions of storytelling or dramaturgy so they can make their subject matter even more politically and emotionally relevant to their public.

Did any themes or ideas particularly stand out to you while working on these books?

Many of the plays in the anthology attempt to lift contemporary experiences of migration, exile, and seeking refuge to mythological dimensions. Others use historical archetypes and figures to talk about today.

What stood out was the issue of generational memory and the need for third/fourth generation Canadians to set the history of their family’s displacement right, to make sure their own children know how to tell this story and how to see it from many points of view.

In the plays written by the first-generation immigrants, the sense of home is distinctive, their trauma from the flight is raw, and their memories of the past are marked by their immediate experiences of the present as well as their hard work of learning a new language and the new ways of life in exile. Often these experiences are accompanied by frustration, hopes crushed, and other difficult processes of becoming someone different.

What should we look forward to in terms of new Canadian plays?

Canadian dramaturgy is rapidly developing in its tools and genres, specifically when it comes to tackling such difficult social issues as immigration.

One of the most popular devices it uses is testimonial drama narrated by immigrants and/or their children that speaks of the dangers and losses from flight and displacement, as well as broken selves and divided identities. This kind of dramaturgy is necessary and will continue to flourish, as it helps immigrant artists tell their stories, and, by doing so, claim their place on the Canadian theatre scene.

Experimental dramaturgy will also continue to be written. As Canadian cities become more and more multicultural and multilingual, there will be more plays seeking to authentically represent this phenomenon on stage. The same goes to the multicultural dramatis personae and casts that will be called on to authenticate this diversity even further.

I also hope we will see more scripts reflecting cultural encounters in the rehearsal hall, as theatre makers of different cultural backgrounds would practice making theatre by interweaving the techniques from their home cultures with more traditional Western forms. I hope in this process of dialogue and exchange there will be more space for meetings between immigrant and Indigenous theatre artists as well.

Need to know more? Get your copies of Theatre and (Im)migration and Scripting (Im)migration now!

Comments